When I left my faith, and the church, it was like…it was like there was still a part of me, maybe a small part, still standing in the foyer outside of the sanctuary. I heard the worship music. Through the shut doors, I could still feel those echoes of sermons.

I wanted to bridge the gap between us. Nothing had happened the way that I was told it was supposed to. I didn’t lose my faith for the reasons we said people did, and none of the supposed “sins” I was doing were like how we said they were like.

I started blogging when I was still a Christian. It was 2009 or 2010, I can’t remember anymore. I wrote with my fellow Christians in mind. When I started losing my faith, I still did—I wanted to say here I am, remember me? Can you hear me at all?

Losing your faith is a slow trickle. I stopped believing in God before I stopped believing in hell and I still believed in hell when I stopped fearing demons. I don’t know when I stopped believing that I had a “call” on my life. My writing always felt like that, like I had the skill, the clarity, the sincerity to ask my former Christians to see the world from my side. Understanding that I could never do that, that nothing I said or did, could ever make my former faith see me, listen, understand, and believe in my own sincerity, and the work and reasoning that went into the decisions I made, well, that might have been the last thing to go.

A part of me was standing in the foyer. Still carrying all the pieces of my faith, this world that had been mine for most of my life. I was the infant in the nursery, the child in Sunday School. A sheep in a church production of We Like Sheep, a member of the choir singing O Come All Ye Faithful in front of our congregation. Summer camps earnestly praying to the Lord. Home groups, as we called them (some churches call them life groups) at various church members houses, running in the backyard playing with other kids, or sitting at my mother’s feet, my Bible open, following along.

A part of me was standing in the foyer. When I’m home alone, the first thing out of my mouth is often singing The Steadfast Love of the Lord. Then it blends into Create in Me a Clean Heart, or As the Deer Panteth, these songs automatic, cut deep into my brain so solidly, they might, in my old age, be the last things I’ll ever remember.

I was the teenager with a thousand questions. We were told: it was the world who made decisions by feelings. The world who thought that thinking too hard, or too freely, was dangerous. Nothing, absolutely nothing we threw at God could deny him. Ask anything, explore anything, because, like the sun, or the ground beneath our feet, no question, no doubt, can risk denying him.

And I did. I asked everything. I was spiritually voracious. Curious, imaginative, praying. I loved the Lord, with a fierce and real love, with an excitement to whatever purpose and plan God had for me.

When I was a teenager, and young adult, my friendships were built on the foundation of Christ. The parks we hung out in, the sleepovers we had, drenched in God-talk. Oh, we were on fire. We were passionate. We wanted truth. We wanted to fill our minds and hearts with whatever was good. Whatever was righteous. I remember them. I remember how sincere we were. I remember the love we said we had. I remember. I remember.

Standing in the foyer. And the worship music, its refrain muffled, but ever present, in the background, the hushed voice of the pastor saying the final prayer nothing but a murmur. My Bible now lives on the top shelf of my bookcase. I have never gotten rid of it. It sits, the leather rotting in disuse, the pages still an archive of my highlights, my struggles, the scriptures that I lived by. Sometimes it comes down off the shelf when my girlfriend and I get the hankering again for a religious discussion, reliving what we once loved; checking scripture against our memories, and asking questions.

But the foyer I’m standing in is the one frozen in my memories. The last year I attended church was 2009. When the doors open, and the people coming pouring out, their children dashing ahead to run on the echoing tile, the laughter and hugs as old friends and new mingle, it’s the late ‘00s.

There are a great many people who would tell me that there is a clear and direct line between those Christians then and now. I understand. I’ve spent the past 10 years critical, angry, rejecting that faith. But I cannot help but feel as though, when the doors to the sanctuary opened, if I had a projector at the ready, playing out this future for them, those 2009 Christians would say what are you talking about that will never be us.

In 2016, I was furious and confused. My girlfriend was heartbroken. Maybe we were too sincere ourselves. Maybe we had been the foolish true believers, not knowing that for those around us, it was a farce. This was the very faith that had formed the foundation of our morality. When we left, we still kept the pieces of it, the ideals of life, and justice, and truth, and hope. Even when we stopped believing in that God, even when we saw our former faith as living contrary to what they said they believed, we still believed. Our eyes still shone with a love of righteousness, justice, truth. And then, it was though someone tapped on the sanctuary walls and they fell, easily, cleanly, like cardboard, revealing the cruelty underneath.

There were heartbroken Christians, too. I remember how many asked: is the Evangelical name salvageable after this? Can we say we stand for anything, argue on a foundation of morality, and be listened to and believed? If they’re still asking those questions, I would like to offer the answer now: no.

That part of me stood in the foyer for so long. Because part of me always had a healthy respect for the sacred, even if I no longer believed in it. And I’ve always held onto the idea of the spiritual human: important, and significant, a single life so special, precious, and rare. That beautiful and almost-contradiction of how numerous we all are, how short our lives, and yet, and yet, the uniqueness of everyone so stunning and worth preserving.

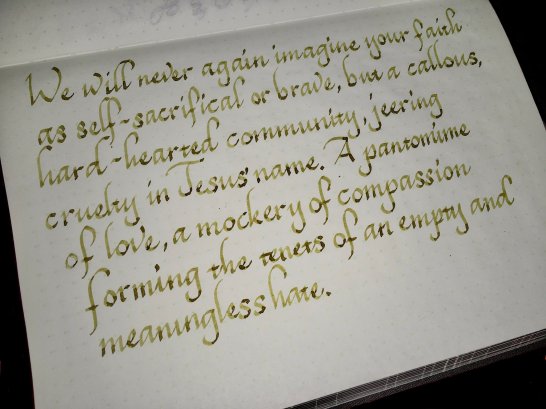

I can’t stand in the foyer anymore. Whatever I held onto, whatever scraps I’ve over the years that left me lingering, holding in suspension the tatter remnants of something of my childhood faith is gone. The sense that there are still good people. The sense that something is salvageable. The sense that I could ever hope to say, look at the damage Evangelicalism caused. Do you care enough, do you love enough, do you want truth and justice enough, to make this better? is all gone.

The doors that open today are not the doors that opened then. The pastors are death preaching to death. The sanctuary walls are rotting, mold and decay blooming and spreading, stained glass shattered on the floor. Their children’s feet are scratched and punctured, their hands grasp and crush the glass through bleeding palms. The worship songs are too loud to hear them crying. The laughter that rolls through the church reeks of death.

And when the doors open, they are skeletons. Their bones crumble against the tile with every step. They grin. They hate. They call their hatred their God. When I left, there were so many Christians who told me that I was rejecting a God fabricated out of the “bad” Christians, the not-really-Christians. That underneath the cruelty, there was a different God. No. This is the God I rejected. And this is the God that they run to.

That’s what’s left of that faith.

And I can’t stand in the foyer anymore.