When my girlfriend read through the draft of my book, she had a comment about how I mention Growing Kids God’s Way only in passing.

When my girlfriend read through the draft of my book, she had a comment about how I mention Growing Kids God’s Way only in passing.

And I realized that I had never explained it, not to her, not to anyone really, anything about Growing Kids God’s Way. It’s not something I’ve seen mentioned on the blogs I read — not that no one is talking about it’s just not something I see with any frequency. Many of the critiques online for GKGW are actually critiques of On Becoming Babywise, a far more well-known book for its controversy related to faithilure to thrive.

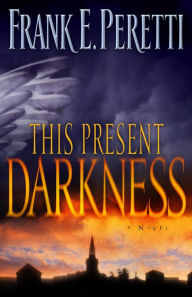

Growing Kids God’s Way by Gary and Anne Marie Ezzo was a parenting class/book that was popular in the ’90s and it promises, as is obvious by the title, that if you implement their methods, you’ll be implementing godly methods of raising your children. And as I sat down to write it, all the various aspects of it came flooding back. First-time obedience. Cheerful obedience. My mothers voice explaining to us, delayed obedience is disobedience. You come when you are called, you respond instantly to your parents voice, and in everything they ask you to do, you show that you are glad to do it. If you absolutely cannot do something, your only recourse is to look your parent in the eye and politely state, “May I make an appeal?”

This was the prize of the Christian parent, the example that you set for the world. Well-behaved children were proof of your faith itself. The world would compare your family to their own unspanked, disruptive, screaming, arguing children, and be moved by your testimony of God’s holiness in how you raise your children. Or so it goes. Children were trophies you paraded out on Sunday mornings; everyone knew who the good Christians were, the ones who had children never talked back, never were cranky, never once showed anything but instantly obedience and a polite, cheerful demeanor.

I haven’t talked about this, mostly because it always felt like background noise. As I got older, my mother stopped specifically mentioning GKGW, and it felt like it vanished, like it had never been much of a big deal to begin with.

All this time I’ve been writing, what nagged in the back of my mind was the how. How did my mother turn me into a person who felt like I had no sense of identity a part from her? How did I become a person that didn’t rebel, didn’t form a sense of identity, didn’t become anything that I didn’t think would meet with her approval? I couldn’t seem to find the beginning of what happened to make me so compliant.

And then I started writing about Growing Kids God’s Way, and all of a sudden the answer was right in front of me: as a young child, my mother started training me to be the kind of person that was nothing a part from obedience. That my moral goodness was tied to how happy of a front I presented. Disobedience was sin and obedience — to parents, and to God — was the highest moral imperative.

The reason I haven’t posted this past month is because just a cursory look at all of these things slammed my brain into the ground hard. It opened up old wounds I didn’t know I had, and left me in a kind of depressive, anxiety haze that required me to put everything down for a bit. I’m slowly pulling myself out, a process inhibited by the fact that I still keep making myself sit down with this book, sift through it all, and remember.

My mother used to brag to other parents that I had smartly gleaned the consequences for disobedience from watching my brothers punishments, and knew to avoid it. She’d brag that I was the one child she knew she had raised right. Only occasionally she’d tell me she worried that one day I would have the standard teenage rebellion, far later and with a vengeance.

But instead, I have to fight not to obey. When obedience is the only thing rewarded, when the only praise you ever received is praise for obeying, how are you to know what your own desires are? Your motivations are tied to obedience. When other people are pleased with you, you are pleased with yourself. When others think you are good, you know you have done right. So how do you manage to have a sense of self apart from that obedience? Recently, I told my girlfriend that I should practice declarative sentences, that the only way I would ever be able to feel like I had any real power is if I could say I want or I need without qualification. And then I told her what I wanted for dinner, and proceeded to burst into tears. Something as small as dinner felt like claws raking their way through my brain; I had violated the deep underlying core of my training.

It is possible to make people obedient. It is possible to train children into cheerful, willing obedience, to make it seem as though their own personal self strives and desires for nothing else; as though they weren’t dog-trained into it, but rather that they are responding out of their own want to obey. It just requires breaking someone down, scooping out any sense of self and personhood they might have, and replacing all of it with obedience. And if you change the word “obedience” in that sentence to “Jesus,” I’m not sure the Christian faith I grew up in would find anything wrong or horrifying about it at all. And that is why it was so easy to do.

“Teach him [your child] to obey according to the character of true obedience-immediately, completely, without challenge, and without complaint.” (Growing Kids God’s Way, page 169 of the 2002 edition).